Co-authored with Dr. Daphna Joel of Tel Aviv University

In their recent comment in Nature (reviewed in The New York Times on May 14, 2014), Janine A. Clayton and Francis S. Collins call for a revolution in the fields of animal and cell research (preclinical research), which have mainly studied males or cells derived from male animals. We applaud the NIH’s continued efforts to ensure that funded research has biological and medical relevance for all people and agree that preclinical studies should include both male and female cells and animals. We worry, however, that Clayton and Collins’ timely call will reinforce an underlying, unwarranted belief that males and females are fundamentally different, thus dovetailing with a popular discourse of absolute difference — the idea that “men are from Mars” while “women are from Venus”, or that there is a “female” brain and a “male” brain. Such beliefs can lead scientists to overlook other variables (e.g., height, weight, physical and psychological life experiences, and in humans, gender — that is, the cultural, embodied expression of sex) that may be more important for explaining group differences than sex itself.

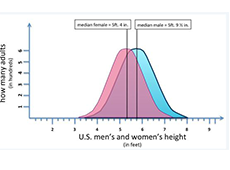

If average differences between males and females result merely from a difference caused, say, by the average sex difference in height, body weight or muscle mass, then smaller men and larger women will be misclassified and, in the medical realm, possibly mistreated. Consider — as do Clayton and Collins — the idea that women should receive a lower dose of the drug zolpidem. Whereas many women may benefit from the lower dose, so would quite a few men, probably; there will also be women who have no problem in continuing to use what is now considered the “male” dose of this drug. In other words, the differences in drug response between men and women are not of the men-from-Mars/women-from-Venus type. Rather, they are mean differences, with plenty of overlap in the distributions of men and women.

The NIH proposal raises additional difficulties. Of course the cells of men and women usually differ with regard to sex chromosomes, and — also quite obviously — the reproductive organs and circulating hormone levels usually differ in male and female bodies. Moreover, in addition to its clear effects on the reproductive system, sex affects other body systems, including bones, the immune system, and the brain. But here matters get complicated. While sex is the most important factor in determining the form of the reproductive system, and most humans come into the world equipped with one of two possible sets of reproductive organs, male or female, in the brain — and probably in other non-reproductive organs — it is a different story. Many animal studies confirm that sex affects brain structure, but they also show that sex is neither the only nor even the main factor affecting a brain’s form or function.

Environmental, developmental and genetic factors play an important role during the processes of brain formation, maintenance and reshaping, from fertilization until death. Moreover, such factors can completely reverse the effects of sex. Thus, what is typical in one sex under one set of conditions (e.g., no stress) may be typical in the other sex under another set of conditions (e.g., chronic stress). Of course, this doesn’t happen in mammalian genitals; they do not flip from a male form to a female form or vice versa. But the malleability of sex-related brain physiology has been documented by many researchers, for many brain features, in vast brain regions, and following a multitude of manipulations. Complex interactions between genes (not only on the sex chromosomes), hormones (not only the so-called sex hormones), and environment produce heterogeneous brains that cannot be grouped into “male” brains and “female” brains. Whether the brain of a male and the brain of a female will differ and in what respect depends on the specific genetic composition and individual histories of the particular male and the particular female animal.

Thus, even in animal models the effects of sex beyond the reproductive system are neither fixed nor absolute. To do good preclinical science that takes into account individual differences in reactivity to drugs or responses to other treatment methods, one clearly has to include both males and females and study sex as a factor, but one should not a priori assume that sex is the most important factor. In humans, one’s sex affects many aspects of one’s communal environment, creating a feedback loop between sex and social experience that we call gender. Gender’s effects should clearly be taken into consideration when attempting to study the effects of sex on health and disease. Good science should be devoted to understanding the suite of factors that explain individual physiological differences, whether we are talking about cells in culture, rodents or humans. We should not replace one mistake — treating males as the norm — with another — treating males and females as two distinct entities. If we are going to insist on a science of difference, let’s do it right.